Learn how AI systems push Kafka to ClickHouse beyond what most pipelines were built for.

Written by

Armend Avdijaj

Jan 21, 2026

I have not met an AI company that planned to spend much time thinking about streaming ingestion.

Most teams start with a product problem. LLM observability, model evaluation, fraud detection, search, or some internal AI workflow that needs to work reliably at scale. Kafka and ClickHouse enter the picture because they are practical tools that solve real problems, not because anyone is excited to operate ingestion pipelines.

Early on, the setup usually feels straightforward. Events flow into Kafka. A consumer reads them. Data lands in ClickHouse. Queries are fast, dashboards look good, and the system feels stable enough to forget about. The team moves on to shipping product features, which is exactly what they should be doing.

The trouble starts much later, when the system is already trusted and relied upon. At that point, Kafka-to-ClickHouse pipelines tend to fail in subtle, slow, and hard-to-diagnose ways.

This post is about those failures and why they show up so consistently in AI systems.

Why Kafka and ClickHouse show up in almost every AI stack

The combination makes sense. Kafka is designed to handle large volumes of unordered events. ClickHouse is designed to answer analytical questions quickly over large datasets. AI systems generate an enormous amount of event data, including LLM calls, traces, token counts, evaluation results, embeddings, feature values, and user interactions. Very little of that data belongs in transactional databases.

Streaming it into ClickHouse feels like the right choice, and in many ways it is. The pattern shows up across AI tooling companies, enterprise AI platforms, internal ML systems, and research environments. The product differs, but the ingestion architecture usually looks the same.

There is almost always custom code sitting between Kafka and ClickHouse. Sometimes it is a single consumer. Sometimes several. It is usually written quickly and rarely revisited once it works. Until it stops working in ways that matter.

These are (in my experience) the lies everyone tells themselves about using Kafka with ClickHouse.

The schema will eventually settle.

We can always backfill later.

If something breaks, we’ll notice.

Kafka and ClickHouse are doing the hard work.

Our current setup is stable enough.

Ingestion is just plumbing.

We’ll clean this up when we have time.

Schema evolution never slows down

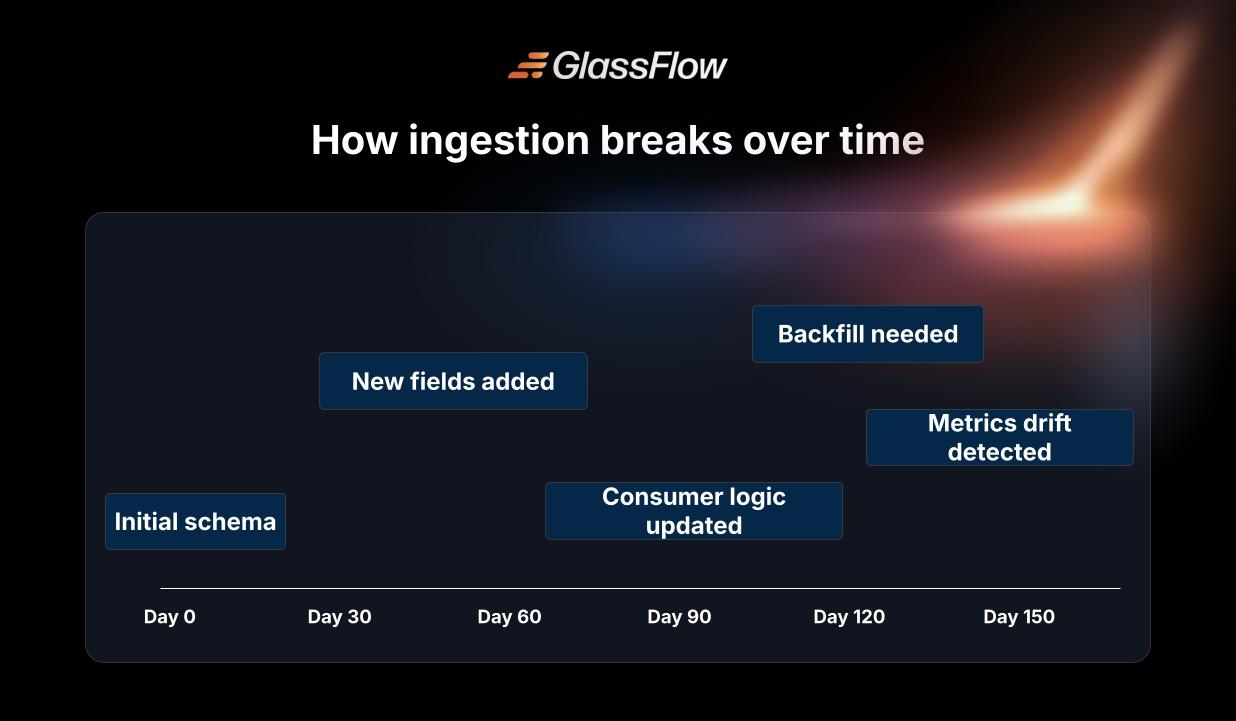

One assumption tends to fail early: the idea that event schemas will eventually stabilize.

In AI systems, schemas change constantly. Models evolve. Instrumentation evolves. New metrics appear. Old fields become irrelevant. Different teams add fields for different reasons, often without coordinating closely.

At first, this is manageable. A new column is added to ClickHouse. The consumer is updated. Everyone moves on.

Over time, Kafka accumulates multiple versions of the same event. Fields are optional. Some events are missing data that newer ones include. Semantics drift slowly. The consumer code grows more defensive and more fragile, and fewer people feel comfortable modifying it.

ClickHouse continues to accept the data without complaint. That flexibility is useful, but it also hides problems until they surface elsewhere.

Backfills sound easier than they are

Another common assumption is that data can always be reprocessed later.

In theory, Kafka makes this easy. You rewind offsets and replay the data. In practice, backfills are one of the riskiest operations in the system.

Reprocessing old events into ClickHouse means dealing with duplication, ordering, schema mismatches, and partial failures. Tables already contain newer data, and merging historical corrections safely is rarely trivial. Dashboards, alerts, and downstream jobs all depend on the outcome being correct.

I have seen teams delay necessary backfills because nobody wanted to take responsibility for the result. Not because they were careless, but because they understood how much could go wrong.

In AI systems, backfills are not exceptional. They are routine. New evaluation logic, new parsing rules, new metrics, and new models all create reasons to replay data. When reprocessing feels dangerous, it usually means the ingestion layer is already stretched too thin.

Silent failures are the hardest to detect

Loud failures are inconvenient, but they are visible. Silent failures are worse. These tend to come from the same sources. Consumers restart with incorrect offsets. Batch inserts partially succeed. Retries create duplicate rows. Schema mismatches drop fields without raising errors.

Everything looks healthy from the outside. Kafka continues to move. ClickHouse continues to ingest. Queries return results.

Weeks later, someone notices that metrics no longer line up with expectations. At that point, it is often unclear when the problem started or which part of the pipeline introduced it.

Once trust in the data erodes, teams spend a lot of time rebuilding confidence instead of building product.

AI products feel these issues earlier

Many analytics systems tolerate a degree of inconsistency. AI products generally do not.

LLM tooling depends on accurate traces and reproducible results. Evaluation pipelines depend on consistent historical data. Model behavior is hard enough to reason about without uncertainty in the underlying events.

AI systems also change more quickly than most software systems. Models, prompts, and instrumentation evolve continuously. The ingestion layer is forced to adapt to that pace, whether it was designed for it or not.

Most Kafka to ClickHouse pipelines were built for a calmer environment.

The issue is not the tools, but the boundary between them

Kafka and ClickHouse are not the problem. Both are reliable and well understood.

The issue is that the responsibility for correctness, evolution, and reprocessing ends up embedded in custom consumer code. That code slowly accumulates complexity and becomes difficult to reason about, especially under change.

Eventually, teams stop asking whether the pipeline is correct and start asking whether it is stable enough to avoid touching. That shift usually signals growing operational risk.

What changes when teams gain experience

Teams that have dealt with these issues tend to change their approach.

They treat ingestion as a system in its own right, not as a side effect of analytics. Schema changes become something the system expects. Reprocessing becomes routine rather than exceptional. Delivery guarantees become explicit instead of assumed.

As a result, ingestion becomes predictable and easier to reason about. Dashboards stabilize. Backfills stop being feared. Engineers regain confidence in the data.

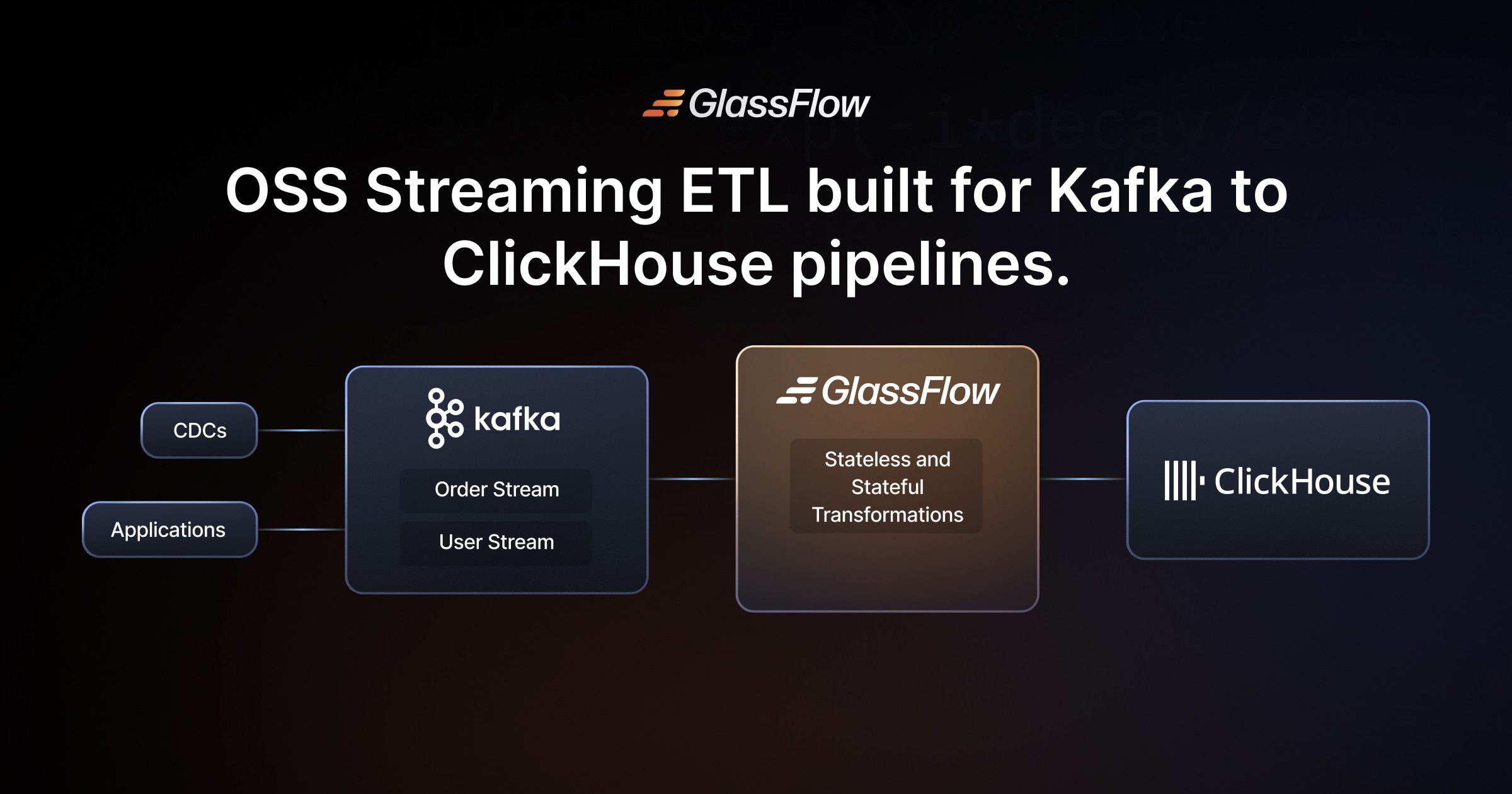

Where GlassFlow fits into this picture

GlassFlow exists because these problems kept appearing in otherwise well designed systems.

Rather than replacing Kafka or ClickHouse, GlassFlow sits between them and takes responsibility for the parts that custom consumers struggle with over time. Schema evolution, reprocessing, and delivery guarantees are handled by the ingestion layer itself instead of being scattered across application code.

Teams configure GlassFlow once and let it absorb the constant change that AI systems produce. The rest of the architecture remains the same.

What it looks like in practice

Most teams start small. They choose one Kafka topic and one ClickHouse table, usually one that has already caused friction. GlassFlow handles offsets, schema differences, retries, and replays without requiring custom consumer logic.

The goal is not a new architecture. The goal is to reduce the number of things that can go wrong quietly.

If you want to try this yourself

If you are running Kafka to ClickHouse today, the fastest way to evaluate GlassFlow is to put it in front of a single real pipeline.

Choose something that already matters. You can stream data into ClickHouse through GlassFlow in under an hour. If the pipeline becomes easier to reason about and less stressful to operate, you will know quickly whether it is worth expanding. If not, you will still have learned where your ingestion risk actually sits.

Did you like this article? Share it!

You might also like

Transformed Kafka data for ClickHouse

Get query ready data, lower ClickHouse load, and reliable

pipelines at enterprise scale.