This is what happens when vertical scaling becomes your bottleneck

Written by

Armend Avdijaj

Feb 12, 2026

Most observability stacks don’t start complicated.

You have Kafka, maybe S3, and you need data in ClickHouse. Vector is an obvious choice. It is fast, it behaves predictably, and it does not require a PhD to operate. You wire it up, add a few transforms, and logs start flowing. For a while it feels like the most boring part of the system, which is exactly what you want from ingestion.

The problems usually show up later, and not all at once.

Traffic increases. Someone adds heavier transforms because raw logs are messy. A product team wants deduplication because retries are polluting dashboards. Someone else asks for a longer aggregation window. None of these changes are dramatic on their own. They just accumulate.

At some point you realize that the ingestion layer is no longer plumbing. It is carrying business logic. It is holding state. It is on the critical path for customer facing queries. And that is where things start to feel different.

When Scaling Stops Feeling Linear

One of the first hints is that scaling stops feeling linear.

You add cores and expect more throughput. Sometimes you get it. Sometimes you get almost nothing. CPU usage does not look catastrophic. Memory is fine. Yet throughput flattens or latency gets unpredictable under load.

This usually surprises people because the machine does not look “maxed out.” But saturation is not always about raw CPU or RAM. It is often about coordination.

Vector moves events through a shared pipeline. Even if you increase worker counts, those workers still coordinate around:

bounded channels

internal buffers

scheduling in the async runtime

batching and flushing in the sink

As throughput rises, the cost of that coordination rises too.

Lock contention increases. Atomic operations become more frequent. Cache coherence traffic grows between cores. Threads compete for shared queues. The sink may serialize batches through a limited number of write paths. None of these on their own look catastrophic in metrics, but together they create a ceiling.

At some point, adding more cores mostly increases coordination overhead rather than useful work. You see CPU available, but effective throughput stops scaling.

That plateau is not random. It is the natural behavior of a shared pipeline architecture under high concurrency.

A Shared Flow Has Coordination Costs

Vector’s model is straightforward. Events move through stages connected by bounded channels. It is clean. It is understandable. But it is still a single logical flow of data.

Even with multiple workers, events are not strongly partitioned with isolated ownership. They pass through shared components. Buffers are bounded and shared. Backpressure is shared. The sink is shared.

When load is moderate, this works extremely well. As load climbs, shared components become pressure points.

You can tune around it. Increase workers. Adjust buffer sizes. Split pipelines. Sometimes that buys you headroom. Sometimes it just moves the bottleneck from one stage to another.

What you do not get is isolated partitions progressing independently. Everything is still part of one larger current.

Backpressure and Blast Radius

Backpressure is where this becomes visible.

Bounded buffers are a good design decision. They keep memory under control and make overload explicit. But in a linear flow, backpressure is contagious.

If ClickHouse slows down for a minute, maybe merges are heavy or network latency spikes, the sink buffers fill. The transform stage cannot drain. Upstream buffers fill next. Before long the source itself slows. The entire pipeline reacts as one unit.

That behavior is technically correct. It is doing exactly what it was built to do. The issue is blast radius.

In a shared pipeline, a localized slowdown rarely stays localized. A transient issue in one stage affects everything upstream. At high sustained ingestion rates, small hiccups turn into visible lag.

At modest scale you barely notice this. At larger scale, tolerance for jitter shrinks.

Nothing is broken. The architecture is simply honest about how it handles pressure.

When State Enters the Picture

State is where things really start to strain.

Stateless transforms are easy. Parse, rename, drop. Even short windows are manageable. Aggregating over a few seconds is not scary.

But once you try to hold state for minutes, maybe to dedupe retries or join streams, you are in a different world.

That state usually lives in memory. If the process dies, that state is gone. If cardinality grows unexpectedly, memory grows with it. There is no natural concept of partition ownership with durable checkpoints the way you would see in a purpose built streaming engine.

You can build safeguards. You can constrain windows. You can accept partial guarantees. Teams do this all the time. But it starts to feel like you are layering streaming semantics on top of a system that was designed primarily for log movement, not distributed state management.

Short windows feel safe. Longer windows feel fragile.

ClickHouse Amplifies the Edges

ClickHouse adds another layer.

It is extremely fast, and that speed can hide weaknesses for a long time. Inserts scream through until they do not. Merges kick in. Disk pressure changes. Insert latency fluctuates.

When that happens, your ingestion layer has to absorb the variability.

If ingestion and sink are tightly coupled through shared backpressure, fluctuations in ClickHouse behavior ripple upstream. Under sustained load those ripples show up as ingestion lag, uneven throughput, or retries cascading through the pipeline.

When ingestion feeds dashboards customers rely on, those ripples are not academic. They show up as stale data and support tickets.

When Ingestion Becomes Critical Infrastructure

There is another shift that happens quietly.

At the beginning, the ingestion layer is just a transport. If it goes down briefly, you restart it. If something misbehaves, you check logs and move on.

Later, ingestion becomes business critical.

Now you care about:

deterministic recovery after crashes

guarantees around duplicate handling

upgrade safety

predictable failure modes

response time when something breaks

At that stage, the conversation changes. You are not only evaluating technical characteristics. You are evaluating operational guarantees.

Open source tools can be excellent pieces of software, but they do not inherently come with service level agreements, escalation paths, or contractual support. When ingestion is feeding customer visible systems, that gap starts to matter. You need to know who owns the failure when it happens at 2 a.m., and what guarantees exist around response and resolution.

That concern does not show up in early prototypes. It shows up when the pipeline becomes core infrastructure.

The Design Envelope

None of this is a critique of any particular tool. It is about design envelopes.

Log shippers optimize for moving data reliably with bounded memory and straightforward operational behavior. Streaming engines optimize for partitioned state, recovery, isolation under load, and durable guarantees.

There is overlap between those worlds, but they are not identical.

The trouble starts when responsibilities shift quietly. The log pipeline becomes responsible for correctness guarantees, long lived state, high sustained throughput, and customer visible reliability. It becomes infrastructure that other systems depend on, not just a conduit.

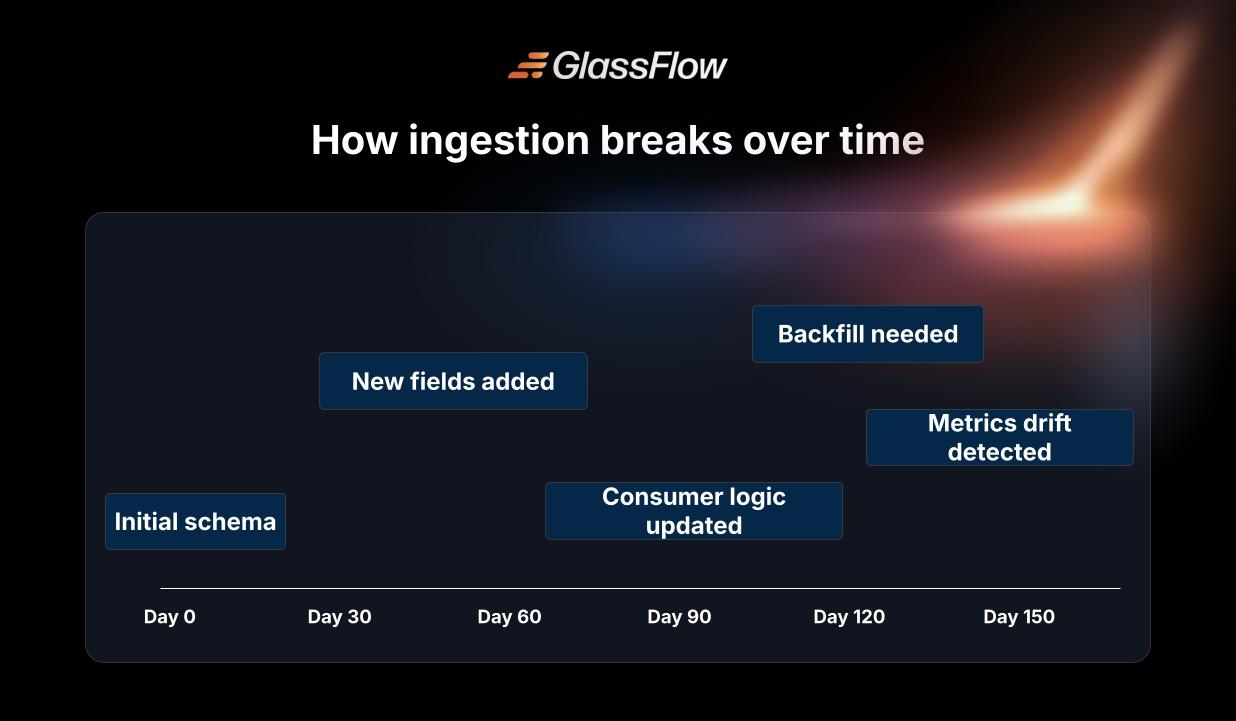

That shift does not happen in a single meeting. It happens feature by feature.

The Questions That Eventually Surface

Eventually you find yourself asking different questions.

If one key is hot, does it stall everything else?

If a node crashes, how much state do we lose?

If we rebalance, where does the state go?

If the sink slows down, do all partitions feel it equally?

If something breaks at night, who is accountable for fixing it?

Those are streaming system and infrastructure questions.

If your ingestion layer does not have clear answers, you are likely operating beyond what it was originally shaped for.

Recognizing that moment early can save a lot of reactive tuning later. Not because anything is defective, but because the job changed and the architecture did not.